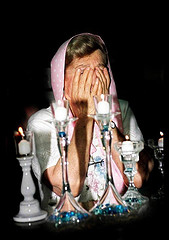

Blessed are You, LORD, our God, King of the universe, who has sanctified us with His commandments and commanded us to light Shabbat candle[s].

Many of us have heard these words spoken on Friday nights in honor of Shabbat (Sabbath). Many non-Jews have also heard this brachah (blessing) in movies, videos, plays, synagogues, etc. But where does this brachah come from and why do Jews all over the world continue to say it every Friday night?

According to tradition, it was Sarah who instituted the idea of lighting Shabbat candles on Friday night. The candles supposedly burned from one Friday night to the next inviting people to visit her and Avraham in their tent.1 Of course, this is only a midrash and is not to be taken seriously so what reasons are given for lighting Shabbat candles?

The first reason given by the sages for lighting Shabbat candles is Shalom Bayit (peace in the home). Shabbat is intended to be a weekly break and peace-filled time from the chaos of our weekly world. Lighting Shabbat candles brings light into the home and thus peaceful rest from the chaos and darkness. A second reason is for pleasure. In order to have pleasure and enjoy the meals and hospitality of a home on Shabbat, lighting – in this case candles – is necessary. A third reason given for this tradition is to honor the day. This tradition more specifically specifies honoring the “Shabbat haMalkah (Shabbat Queen).”1 Since ancient times Shabbat has been personified as a bride or queen that is to be welcomed in during the waning of the day. In the sixteenth-century Kabbalat Shabbat (Welcoming the Sabbath) was created and the Shabbat haMalkah became affixed in Friday night rituals.2

Lighting Shabbat candles on Friday night is an ancient ritual and is mentioned as one of three things that must be done before Shabbat begins in the Mishnah (Shabbat 2:7). The rabbis believed that Shabbat was to be a day of delight as spoken of by Yeshayahu (58:13). In order for the day to be a delight the home must have light and warmth. Thus the rabbis instituted the lighting of candles before Shabbat began. The idea behind the lighting of these candles was to ensure that there was light and warmth available during Shabbat since the kindling of fire was prohibited on Shabbat.2

You shall kindle no fire throughout your settlements on the sabbath day. (Shemot 35:3)3

This mentioning of lighting candles before Shabbat began in the Mishnah however was only for Shalom Bayit and not the mitzvah we see today. In the Geonic Period (eighth-ninth centuries) a dispute arose between the Rabbinic Jews and the Karaite Jews. While the Rabbinic Jews followed the Mishnah and lit candles on Friday nights – and permitted these candles to continue to be lit through Shabbat – the Karaite Jews taught that all lights must be extinguished before Shabbat began.2 In order for the Rabbinic Jews to demonstrate that fire and light were permitted on Shabbat (if they were lit before Shabbat) the rabbis instituted the Shabbat candle-lighting ceremony. The rabbis thus transitioned the Shabbat candle-lighting from one of Shalom Bayit to a mitzvah complete with a bracha.4 The bracha for Shabbat candle-lighting was established by the Geonim as a reaction to the Karaite teachings. The bracha “that they formulated was similar to the ancient one used when lighting the Hanukkah lights.”2

We are not commanded to light either the Hanukkah candles or the Shabbat candles in the Torah. The Geonim however justified the action of making this ceremony and bracha a mitzvah by using the following verse of Torah.

You shall act in accordance with the instructions given you and the ruling handed down to you; you must not deviate from the verdict that they announce to you either to the right or to the left. (Devarim 17:11)3

The Geonim thus concluded that “whatever the later legitimate authorities decide, based upon their interpretation of the Torah or upon their understanding of ancient practice, is the will of God.”2

The Geonim, based in Babylonia, were the leaders of the diaspora Jews and were the ones who ultimately made rulings of halakhah that were accepted by diaspora Jewry. The Babylonian schools were the leading places of learning and the heads of these schools were recognized as the highest authorities in halakhah.

The rulings of the Geonim were to be treated as the “modern” rulings of the judges who were to preside over Yisrael as seen in Devarim. However, smicha had already become corrupted by this time – there was very little chance that one could trace his smicha back to Moshe. The Geonim were not part of an organized Sanhedrin, there was no Temple and no priests to be advisors, and the Geonim were ruling from outside Eretz Yisrael. Ultimately, they had no legitimacy to demand that their rulings become halakhah for all of Yisrael. The verse used from Devarim to legitimate the rulings of the Geonim is taken out of context. It clearly states in Devarim chapter 17 that the magistrate and the levitical priests are to be consulted in a “place that the LORD your God will have chosen.”3 It also states in this chapter that the levitical priests and/or magistrate are to be consulted if “a case is too baffling for you to decide, be it a controversy over homicide, civil law, or assault – matters of dispute in your courts.” So the entire legitimacy of the Geonim to declare halakhah for the entire Jewish people is undermined if one reads this entire chapter of Devarim. The Geonim had no right to declare halakhah and no right to declare a new mitzvah.

I personally reject the idea of lighting Shabbat candles under the auspices of a “mitzvah.” The “mitzvah” is illegitimate and is a chillul Hashem (desecration of God’s name). If one truly wants to honor Shabbat and also wants a personal ceremony to help usher in the Shabbat then this is an optional tradition – but it must not transgress Torah.

——————–

1“Blessing and Instruction for Shabbat Candles.” chabad.org. Chabad, n.d. [http://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/87131/jewish/Shabbat-Candles-Instructions.htm]

2Reuven Hammer. “Or Hadash: A Commentary on Siddur Sim Shalom for Shabbat and Festivals.” New York: The Rabbinical Assembly, 2003.

3David Stein (ed.). JPS Hebrew-English Tanakh. Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society, 1999.

4Haggai Zagury. “Shabbat Candles.” reflectingonjudaism.com. Reflecting on Judaism, August 2003. [http://www.reflectingonjudaism.com/Shabbat_Candles]