The Mishnah is a compilation of legal opinions and debates. Statements in the Mishnah are typically terse, recording brief opinions of the rabbis debating a subject; or recording only an unattributed ruling, apparently representing a consensus view. The rabbis recorded in the Mishnah are known as Tannaim. Since it sequences its laws by subject matter instead of by biblical context, the Mishnah discusses individual subjects more thoroughly than the Midrash, and it includes a much broader selection of halakhic subjects than the Midrash. The Mishnah’s topical organization thus became the framework of the Talmud as a whole. But not every tractate in the Mishnah has a corresponding talmud. Also, the order of the tractates in the Talmud differs in some cases from that in the Mishnah. In addition to the Mishnah, other tannaitic teachings were current at about the same time or shortly thereafter. The Gemara frequently refers to these tannaitic statements in order to compare them to those contained in the Mishnah and to support or refute the propositions of Amoraim. All such non-Mishnaic tannaitic sources are termed baraitot (lit. outside material, “Works external to the Mishnah”; sing. baraita). The baraitot cited in the Gemara are often quotations from the Tosefta (a tannaitic compendium of halakha parallel to the Mishnah) and the Halakhic Midrashim (specifically Mekhilta, Sifra and Sifre). In the three centuries following the redaction of the Mishnah, rabbis throughout Palestine and Babylonia analyzed, debated, and discussed that work. These discussions form the Gemara. Gemara means “completion” (from the Hebrew gamar: “to complete”) or “learning” (from the Aramaic: “to study”). The Gemara mainly focuses on elucidating and elaborating the opinions of the Tannaim. The rabbis of the Gemara are known as Amoraim (sing. Amora). Much of the Gemara consists of legal analysis. The starting point for the analysis is usually a legal statement found in a Mishnah. The statement is then analyzed and compared with other statements used in different approaches to Biblical exegesis in rabbinic Judaism (or – simpler – interpretation of text in Torah study) exchanges between two (frequently anonymous and sometimes metaphorical) disputants, termed the makshan (questioner) and tartzan (answerer). Another important function of Gemara is to identify the correct Biblical basis for a given law presented in the Mishnah and the logical process connecting one with the other: this activity was known as talmud long before the existence of the “Talmud” as a text. The Talmud is a wide-ranging document that touches on a great many subjects.

Traditionally Talmudic statements are classified into two broad categories, halakhic and aggadic statements. Halakhic statements directly relate to questions of Jewish law and practice (halakha). Aggadic statements are not legally related, but rather are exegetical, homiletical, ethical, or historical in nature. In addition to the six Orders, the Talmud contains a series of short treatises of a later date, usually printed at the end of Seder Nezikin. These are not divided into Mishnah and Gemara. The process of “Gemara” proceeded in what were then the two major centers of Jewish scholarship, the Land of Israel and Babylonia. Correspondingly, two bodies of analysis developed, and two works of Talmud were created. The older compilation is called the Jerusalem Talmud or the Talmud Yerushalmi. It was compiled in the 4th century in Israel. The Babylonian Talmud was compiled about the year 500 CE, although it continued to be edited later. The word “Talmud”, when used without qualification, usually refers to the Babylonian Talmud. While the editors of Jerusalem Talmud and Babylonian Talmud each mention the other community, most scholars believe these documents were written independently. The Jerusalem Talmud was one of the two compilations of Jewish religious teachings and commentary that was transmitted orally for centuries prior to its compilation by Jewish scholars in Israel. It is a compilation of teachings of the schools of Tiberias, Sepphoris and Caesarea. It is written largely in a western Aramaic dialect that differs from its Babylonian counterpart. This Talmud is a synopsis of the analysis of the Mishnah that was developed over the course of nearly 200 years by the Academies in Israel (principally those of Tiberias and Caesarea.) Because of their location, the sages of these Academies devoted considerable attention to analysis of the agricultural laws of the Land of Israel.

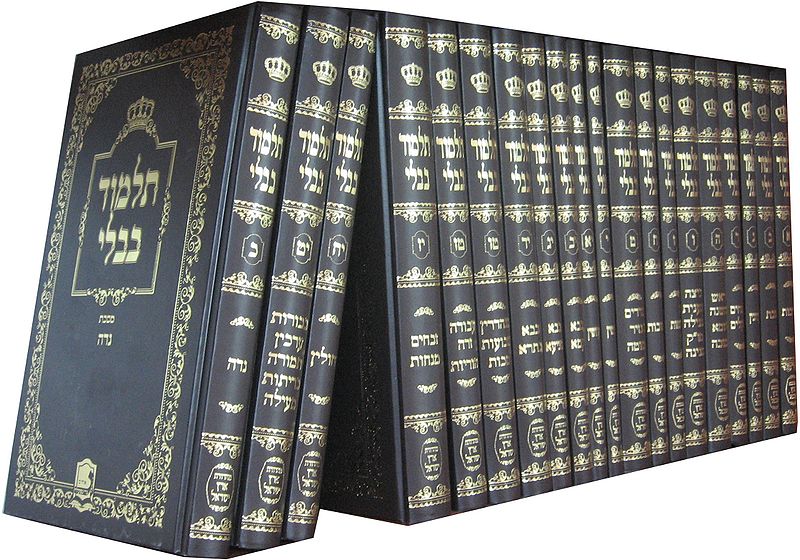

Traditionally, this Talmud was thought to have been redacted in about the year 350 CE by Rav Muna and Rav Yossi in the Land of Israel. It is traditionally known as the Talmud Yerushalmi (“Jerusalem Talmud”), but the name is a misnomer, as it was not prepared in Jerusalem. It has more accurately been called “The Talmud of the Land of Israel”. Its final redaction probably belongs to the end of the 4th century, but the individual scholars who brought it to its present form cannot be fixed with assurance. By this time Christianity had become the state religion of the Roman Empire and Jerusalem the holy city of Christendom. In 325 CE Constantine, the first Christian emperor, said “let us then have nothing in common with the detestable Jewish crowd.” This policy made a Jew an outcast and pauper. The compilers of the Jerusalem Talmud consequently lacked the time to produce a work of the quality they had intended. The text is evidently incomplete and is not easy to follow. The apparent cessation of work on the Jerusalem Talmud in the 5th century has been associated with the decision of Theodosius II in 425 CE to suppress the Patriarchate and put an end to the practice of formal scholarly ordination. Despite its incomplete state, the Jerusalem Talmud remains an indispensable source of knowledge of the development of the Jewish Law in Israel. It was also an important resource in the study of the Babylonian Talmud by the Kairouan school of Hananel ben Hushiel and Nissim Gaon, with the result that opinions ultimately based on the Jerusalem Talmud found their way into both the Tosafot and the Mishneh Torah of Maimonides. Following the formation of the modern State of Israel there is some interest in restoring Eretz Yisrael traditions. For example, Rabbi David Bar-Hayim of the Makhon Shilo institute has issued a siddur reflecting Eretz Yisrael practice as found in the Jerusalem Talmud and other sources. The Talmud Bavli consists of documents compiled over the period of Late Antiquity (3rd to 5th centuries). During this time the most important of the Jewish centres in Mesopotamia, later known as Iraq, were Nehardea, Nisibis, Mahoza (just to the south of what is now Baghdad), Pumbeditha (near present-day al-Anbar), and the Sura Academy near present-day Falluja. Talmud Bavli (the “Babylonian Talmud”) comprises the Mishnah and the Babylonian Gemara, the latter representing the culmination of more than 300 years of analysis of the Mishnah in the Babylonian Academies. The foundations of this process of analysis were laid by Rab, a disciple of Rabbi Judah ha-Nasi. Tradition ascribes the compilation of the Babylonian Talmud in its present form to two Babylonian sages, Rav Ashi and Ravina. Rav Ashi was president of the Sura Academy from 375 to 427 CE. The work begun by Rav Ashi was completed by Ravina, who is traditionally regarded as the final Amoraic expounder. Accordingly, traditionalists argue that Ravina’s death in 499 CE is the latest possible date for the completion of the redaction of the Talmud. However, even on the most traditional view a few passages are regarded as the work of a group of rabbis who edited the Talmud after the end of the Amoraic period, known as the Saboraim or Rabbanan Savora’e (meaning “reasoners” or “considerers”). The question as to when the Gemara was finally put into its present form is not settled among modern scholars. Some, like Louis Jacobs, argue that the main body of the Gemara is not simple reportage of conversations, as it purports to be, but a highly elaborate structure contrived by the Saboraim, who must therefore be regarded as the real authors. On this view the text did not reach its final form until around 700. Some modern scholars use the term Stammaim (from the Hebrew Stam, meaning “closed”, “vague” or “unattributed”) for the authors of unattributed statements in the Gemara.

——————–

Source: “Talmud.” wikipedia.org. Wikipedia, n.d. [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Talmud]